Please note, this article contains description of the ICU environment during the pandemic.

In December last year, the pandemic hit again hard. Hospitals were under pressure, faced with high patient numbers. It meant some teams were redistributed in hospitals to places where they were more needed. In January 2021, medical students were called in to assist hospital teams. I was asked to support the intensive care unit (ICU).

Being in my penultimate year of medical school, I had never been to the ICU before. For me, this department was always the unknown, the department on the floor above. I had never been to it but I’d heard so much about it. I’d seen patients come back from ICU, and had seen coverage of ICU in the news. It was scary, but I wanted to help, and I felt ready. This was one way I knew I could support the effort to combat the pandemic.

My role as a volunteer

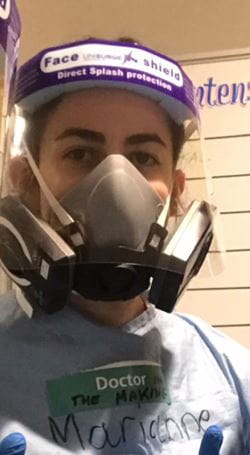

On my first day, I felt nervous but prepared. I had watched the training videos. I knew how to put on and take off the PPE and I had my brand new ‘astronaut’ mask. I was told I would work with the team in charge of proning the patients.

In ICU, most people are unconscious and intubated. But a serious COVID-19 infection can sometimes mean the lungs have trouble getting oxygen, even with a ventilator. One way this was managed on the ward was to turn the unconscious patients onto their stomach to help with respiration. Patients were turned on their front and then turned back once or twice a day. Proning requires a lot of strength, to lift and rotate a completely unconscious patient. It usually requires three or four pairs of hands at the side of the patient: I was going to be one of those pairs of hands!

I was immediately reassured when I met the physio team responsible for proning. They were so welcoming and happy to have me on board with them. I would get to know them well over the next few days. I got dressed in scrubs, then put on mask, sleeved gown, gloves and visor. The team and I were transformed, from a smiling bunch of individuals to a squadron of blue gowned, masked, anonymous warriors.

Our badges were the only means of correctly identifying each other. Breathing required a lot more effort from underneath the big mask and our speech was muffled. It was a bit unsettling and we had to make more efforts to communicate. But there wasn’t much time to think about all that. We had to go in.

Stepping into the COVID-19 ICU

I was surprised by the calm atmosphere in the ICU. People were working hard and busy doing different tasks, but everyone was composed. No one was panicked or disorganised. That was reassuring to me. It was also clear everyone understood their role and was doing their tasks; the doctors checking on patients and how their condition was evolving, one nurse for each patient giving mediations and checking drips, the healthcare assistants helping with patient care.

The team and I were transformed, from a smiling bunch of individuals to a squadron of blue gowned, masked, anonymous warriors.

There were also people I didn’t get to see personally but I knew were working incredibly hard behind the scenes; the porters moving the patients, the store managers making sure the equipment in the cupboard was well stocked, the cleaners who guaranteed immaculate cleanliness of the space. It helped me appreciate how all these people are incredibly important in the hospital team and put their lives at risk for the patients we care for.

Caring with compassion

The team of physios led me to our first few patients. From under all my PPE, I looked at them closely. It was impossible not to feel such a rush of emotions. I now realised the amount of equipment required to take care of them. The ventilator of course, but also the intravenous lines to deliver medication, a feeding tube in their mouth, a catheter for their urine, electrodes on their chest to monitor their heart.

I studied their faces and their features, behind all the tubes and machinery, trying to imagine them when they were well – more themselves, in their everyday lives which I knew little about. What struck me was the vulnerability: unconscious, completely unaware of everything, even of the danger and struggle they were in.

These experiences leave traces and scars on the body and I have seen people come out extremely weakened – their body swollen and achy, needing months of rehabilitation and learning how to live again. There’s also the emotional and psychological impact, that those of us who have not experienced may not understand.

I recognised the importance of the work there, and the implications of my presence. I was honoured to be able to help them, and realised my responsibility to care for them with the upmost respect. The empathy I felt in those moments was stronger than anything I had felt before in medicine.

Working as a team

The work was hard and the day went on. We moved from patient to patient, with the same care and respect every time. I always did my best, helping with the equipment, doing the little tasks that could help, and I felt part of the team.

Throughout my time on the ward, I always felt supported, well supervised and was never pressured or rushed into something I wasn’t comfortable with. It was a steep learning curve but with a gentle team and great support. I learned so much – practical skills and technical things I will need as a doctor working in hospital; like ventilator management, daily patient care, and preventing pressure sores for example.

I also learned and practised the importance of teamwork and communicating. But the most important things I learned during my time on the ICU were the human factors. I was exposed to a raw and challenging environment. I was confronted with vulnerability and suffering, and sometimes even death. But I also witnessed absolutely incredible kindness, compassion and care.

![Hospital beds]()

Photo credit: iStock

During the days I worked in the ICU, my feelings were of true admiration for all the staff. It gave me an incredible insight into the work of my future colleagues, doctors, physiotherapists, nurses, healthcare assistants, pharmacists. I was so proud to be able to work by their side and I hope that one day I will be able to deliver, with the same level of skill and dedication.

On my last day, as I was taking off my equipment for the last time, a doctor came to thank me for my contribution. It was a real gesture of kindness. With those few words, on that cold and bleak February afternoon, I knew I was in the right place. I know my help was just a tiny drop in the ocean, but the ocean is just made of little drops. And the NHS is just made of our NHS workers. I am proud to be part of our NHS and I am so proud of all our efforts.

Dr Marianne Gazet

Marianne is an obs & gynae specialty trainee working in London. She is passionate about medical education and loves developing resources for medical students and doctors. She has recently published an e-book just for new doctors, to help with young doctors' first steps as foundation doctors. She is a content creator and podcast host, sharing her day-to-day life in specialty training as well as advice and tips for others. In her spare time, she loves sports, travelling and learning languages.

See more by Dr Marianne Gazet